Yonathan Netanyahu, the oldest son of Ben-Zion and Zila Netanyahu was born in New York City in 1946. His parents were there to work for the creation of a Jewish state. Yoni, as he was known, was named for a Christian Zionist—Col. John Henry Patterson. In fact, he and Ben-Zion Netanyahu were such close friends that Ben-Zion asked Col. Patterson to be Yoni’s godfather.

Yonathan Netanyahu, the oldest son of Ben-Zion and Zila Netanyahu was born in New York City in 1946. His parents were there to work for the creation of a Jewish state. Yoni, as he was known, was named for a Christian Zionist—Col. John Henry Patterson. In fact, he and Ben-Zion Netanyahu were such close friends that Ben-Zion asked Col. Patterson to be Yoni’s godfather.

I had dinner with Dr. Iddo Netanyahu, the youngest of the three brothers in Jerusalem some time ago, and he told me that in the family home when he was growing up there was a special commemorative bowl with a personal inscription that had been given to the family by Col. Patterson.

After the nation of Israel was reborn in 1948, the Netanyahus moved back to the Jewish state, where Benjamin and Iddo were born. Ben-Zion Netanyahu was working on research, teaching, and editing the first Hebrew encyclopedia while Yoni was in school. The family moved back and forth between Israel and America several times while Yoni was growing up.

He was an outstanding student and was elected as president of the student council at his school in Jerusalem. Ben-Zion returned to America before Yoni’s senior year to teach at Dropsie College in Philadelphia and Yoni graduated from high school in America. The family remained, but Yoni returned to Israel to begin his military service.

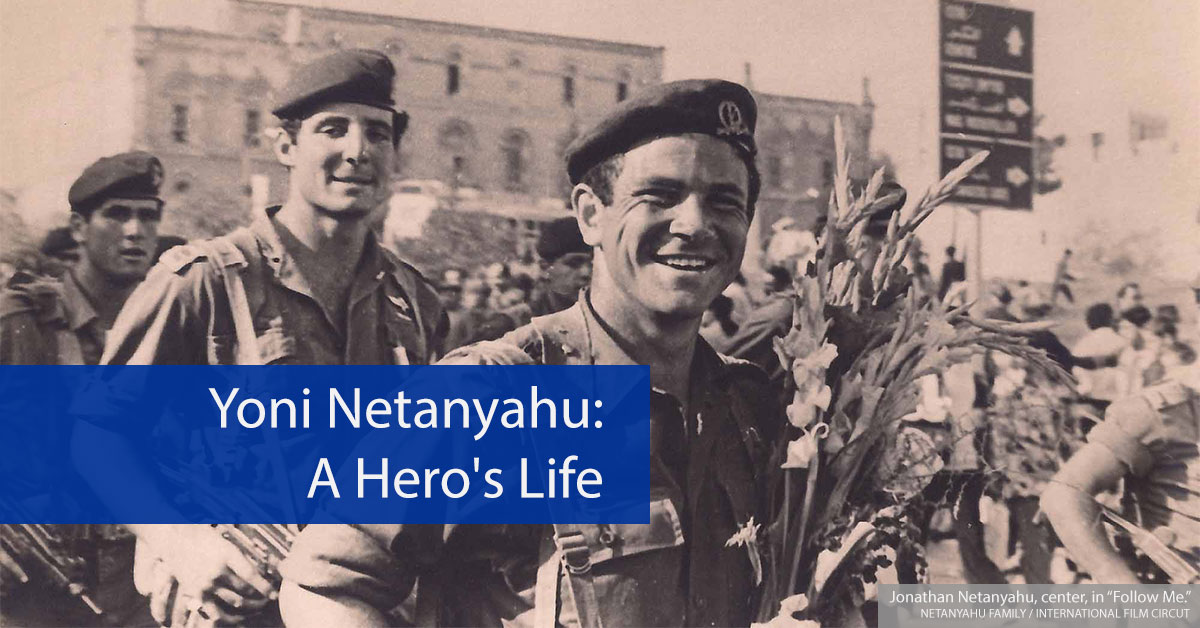

After basic training, Yoni volunteered for service in the paratroopers, and his outstanding performance resulted in his appointment to officers training school. After graduating first in his class, Yoni was given a command position and served his country with courage and distinction. Yoni’s military term of service ended early in 1967, and he had been accepted to attend Harvard starting that fall, but a major war was about to intervene.

With the Six-Day War looming, Yoni along with many other reservists was mobilized and called back to active duty. He fought in the both Sinai against Egyptian forces and then was moved north to face the Syrians in the Golan Heights. During the fighting there, Yoni was wounded as he tried to rescue another injured soldier. He crawled back to the Israeli lines before collapsing. His wounds required two surgeries, and he never fully regained the use of his left arm.

Yoni did make it to Harvard by the fall of 1967 and spent a year there, but then returned to Israel to further his college education at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. The continuing threats facing the Jewish state led Yoni to return to military service, especially in light of the urgent need of the Israeli army for experienced commanders. He was assigned to the Sayeret Matkal, a secret and elite commando unit in which his younger brother Benjamin was already serving. They would soon be joined by Iddo Netanyahu, and the three brothers fought together for two years.

Though most of the operations of the Sayeret Matkal remain classified 40 years later, it is known that Yoni and his unit were very active in fighting against the PLO in the early 1970s, especially after the Black September raid on the Munich Olympics that killed eleven Israeli athletes and coaches. Yoni returned to his studies at Harvard again in 1973 and was able to spend time with his parents as his father was teaching Jewish Studies at Cornell at the time.

The Yom Kippur War saw Yoni called back to service once again. He led Israeli special forces fighting the Syrians in the Golan Heights. Yoni received a distinguished service medal for rescuing a wounded Israeli officer trapped behind Syrian lines. When the war ended, he received command of an armored unit. In 1975, Yoni was appointed as commander of the Sayeret Matkal commando team with which he had served.

On June 27, 1976, an Air France flight leaving Israel was hijacked by Palestinian terrorists and flown to Entebbe, Uganda. The dictator there, Idi Amin, welcomed the terrorists and backed them up with Ugandan troops. More than 100 Israelis were being held. The threat was that they would be killed unless the government released Palestinian prisoners.

On July 1, Yoni was ordered to draw up plans for a potential rescue operation. He and his top advisers quickly considered options. They constructed a mock terminal building so they could assess different approaches. The mission needed to be able to move swiftly so that the terrorists would not kill the hostages once they realized a rescue was underway. In addition, they needed to be able to fight off the Ugandan troops stationed at the airport and prevent reinforcements from keeping them from leaving.

The commando unit rehearsed possible approaches for most of the next day before Yoni went before the leaders of Israel’s military to brief them on the plan. As additional intelligence information about the situation on the ground came in they continued to revise the plan. Finally, Yoni was prepared to offer a confident assessment that the daring raid would succeed. Shimon Peres, then the Defense Minister and later Prime Minister of Israel, recalled their meeting.

“He presented the plan to me in detail, and I liked it very much. The two of us sat alone…My impression was one of exactness and imagination…and complete self-confidence…which without a doubt influenced me. We had a problem with lack of intelligence. But Yoni said: ‘Do you know of any operation that wasn’t carried out half blind? Every operation is half blind.’ But Yoni was well aware of the problem, and he told me that the operation was absolutely doable. And as to the cost, he said we had every chance of coming out of it with almost no losses.”

On July 3, the Israeli government met in secret session and after a lengthy debate approved the plan.

Yoni and his commando team were already on four planes and flying toward Uganda. They would have been called back had the vote gone against the attempt. During the flight, the exhausted Yoni, who had been going non-stop for nearly a week napped on a small bed near the front of the plane.

One of the pilots later described the scene: “He was sleeping like a baby, utterly at peace. I asked Tzvika, the navigator, when Yoni had gone to sleep, and he said, ‘He went to sleep [a while ago] and asked me to wake him up a little while before the landing.’ And the thought flitted through my mind: Where does this calmness of his come from? Soon you’re going into battle, and here you are, sleeping as if nothing is happening! I myself couldn’t fall asleep. I got up and went back to my seat.”

The raid was carefully timed to arrive just after midnight, early in the morning of July 4. The team had procured vehicles like those used by the Ugandan army so that the terrorists would not immediately recognize they were under assault. Nearly everything about the raid worked perfectly as they had planned. For example, as the vehicles advanced down the runway toward the terminal, there were two Ugandan guards exactly where they were expected to be. One of the members of the raid team later said, “When I saw those two guards waiting for us, like the guards that Yoni had placed in the rehearsal, I knew that this operation would succeed.”

As the commandos made their way toward the building, Yoni was seriously wounded by terrorist gunfire. But his soldiers, in keeping with the instructions he had issued before the battle, did not stop to care for him. The safety and rescue of the hostages were their priority. The men made their way inside and killed all of the terrorists. Yoni was still alive when they returned, but the efforts of the doctors on the plane to save his life failed, and he was pronounced dead on the return trip to Israel.

In his diary, Shimon Peres recounted hearing the news: “At four in the morning, Motta Gur came into my office, and I could tell he was very upset. ‘Shimon, Yoni’s gone. A bullet hit him in the heart…’ This is the first time this whole crazy week, that I cannot hold back the tears.”

In the end, 102 of the 106 hostages were rescued alive, and the Israeli commandos only lost one soldier—their leader, Yoni Netanyahu. Yoni’s body was flown back to Israel, and he was buried on Mt. Herzl.

In a letter to his brother Benjamin, written shortly after the end of the Yom Kippur War in 1973, Yoni Netanyahu said: “We’re preparing for war, and it’s hard to know what to expect. What I’m positive of is that there will be a next round, and others after that. But I would rather opt for living here in continual battle than for becoming part of the wandering Jewish people. Any compromise will simply hasten the end. As I don’t intend to tell my grandchildren about the Jewish State in the twentieth century as a mere brief and transient episode in thousands of years of wandering, I intend to hold on here with all my might.”